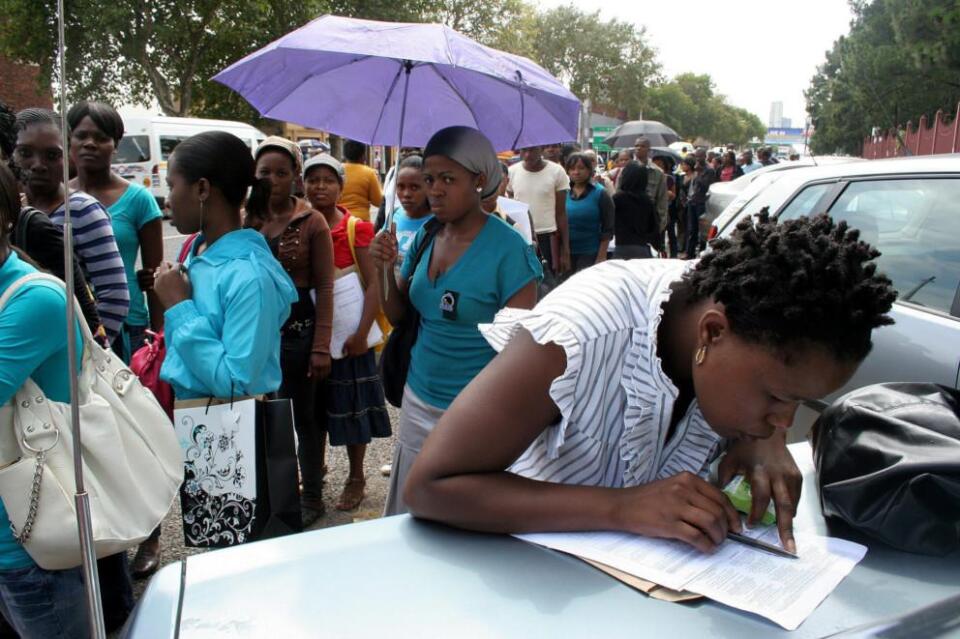

Picture: African News Agency (ANA) – Precious Simelane fills in a job application form at the offices of the Department of Water Affairs in Pretoria. There have been calls to revamp the income grant system.

The South African Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) is scheduled for delivery by the Minister of Finance on 26 October. From a political economy perspective, the MTBPS will indicate whether or not the ANC will be seeking to win the 2024 national and provincial budgets on a pro-poor ticket. Historical allies and voters, COSATU, gave an unambiguous message to the ANC leadership last week at its national congress that it’s support in the ballot box is not guaranteed.

The stubborn hubris of the ruling party does not appear to be waning. The ANC appears to be completely out of touch with the miserable realities of life lived by the majority of their electorate. Their recent policy conference resolution affirms their commitment to a Basic Income Grant and universal social security, and yet Treasury seems aggressively determined to eradicate the meagre R350 grant. This dissonance in the ANC suggests no coherence on key principles and policies.

This coming year will be one of fierce contestation ahead of the 2024 elections. The Young Turks – the new independents – bring with them a freshness untainted by corruption and the arrogance that has settled around the leadership of the ruling party.

If the ANC wanted to secure victory, the one policy that would win the votes and restore the faith of its largely working class and unemployed electorate would be the Basic Income Grant (BIG). Its determination to reject the BIG is one of the own goals that has come to characterise a ruling party that seems more concerned with preserving the wealth of the elite than ending the intergenerational poverty of the majority.

South African poverty levels have grown steeply since 2011 and the unemployment trajectory is also growing, even without the disaster that is load shedding. Economist Duma Gqubule in a recent paper on unemployment published by Social Policy Institute in August, South Africa’s unemployment crisis: a national disgrace.

A plan to achieve full employment by 2035, projects an unemployment rate of 50.9 percent or 17 million people by 2030 unless the state takes significant steps to change the fundamentals of its development path. Gqubule’s plan to achieve full employment in South Africa by 2035 is bold but clear and he sets out in unequivocal detail the interventions needed to reverse the current dystopia.

Gqubule argues that South Africa’s current macroeconomic policy framework will ultimately be the downfall of the country. The macroeconomic policy targets debt and inflation, and these targets are out of kilter with the country’s needs. According to the report, in choosing these targets, the state continues to starve state and household expenditure respectively and growth will never be possible.

Following these targets leads directly to a drop in national demand, and so the economy stagnates.

Rather, he argues, the macroeconomic framework should target growth of 6 percent per annum, and employment. Rather than continuing to cut state expenditure under Treasury’s austerity budgeting he argues for three fundamental policy changes: the introduction of a universal decent Basic Income Grant indexed to the Upper Bound Poverty Line (approximately R1,500 per month), the consolidation and expansion of the many different public employment programmes with a living wage threshold, and the adoption of ‘aggressive industrial policies’ that ‘steer production towards sectors that have high (employment) multipliers’. His modelling based on these reforms predicts an unemployment rate of 4,4% by 2035, or 1,6 million people.

And Gqubule does not, as conservative think tanks have scaremongered, model these reforms on tax increases. Taking money out of the economy is not what he prescribes, rather using other available funds that are sitting unutilised on the ‘SA INC balance sheet’ and increasing debt until these policies start virtuously paying for themselves.

Gqubule is not the only intellectual who has been developing alternatives to help South Africa out of the current state of implosion. But Treasury appears deaf to these analyses.

So, what will we see in the MTBPS?

There was much hope across the country in February 2022 that the meagre R350 Social Relief of Distress (Covid) grants would finally become a permanent policy.

Up until then, recipients seldom knew with certainty whether the grants would continue from month to month or whether they would just dry up, as happened just before the July 2021 riots. And beneficiaries had very concrete grounds for their optimism.

Firstly, social security grants are guaranteed in the Constitution to people unable to provide for themselves, so actually the state is obliged to continue with the grant unless it can prove that the need is not there. Secondly, all the impact evaluations of the grants showed an overwhelmingly positive impact on food intake, on the mental health of the beneficiaries and the local economies as people incredibly used the small grant amount to grow their economic activities and support local business initiatives, and thirdly, Treasury said that it would do so. In the February 2022 budget the Minister of Finance promised that the grants would be extended, in his words: ‘R44 billion is allocated for a 12-month extension of the R350 social relief of distress (SRD) grant’.

So what in fact happened has been a national disgrace, and not the work of a party committed to alleviating the poverty of the majority. The critical words were not the 12 month extension of the relief, but the R44 billion allocation. The budget for the promised extension was ring fenced and the line department, the Department of Social Development, had to create a maze of obstacles to slash eligibility for the 10 million beneficiaries who were receiving the grant at the beginning of the year.

In March 2022, 10,3 million people received for the R350 grant. In April, not a single person received any payment.

In May again, not one R350 grant was paid, bringing utter distress to the good people who had been receiving the grant.

In July, under the new regulations introduced to comply with Treasury’s budget allocation, 3,7 million people were now deemed eligible for the mean R350 grants.

So how does government justify such actions? It seems that clandestine conditions issued by the World Bank that insist on poverty targeting rather than universal benefits are more compelling than the Constitution, or the weight of the empirical evidence of the beneficial returns that the grants were generating. Ironically, under the new Treasury regulations, the means test adjustment meant that anyone who used the grant to make further money lost the grant if their initiative was successful.

In a recent report Can a Leopard change its Spots published by Development Pathways and Act Church of Sweden, the authors track the dissonance between the commitment by the World Bank leadership to support universal social protection in signing the USP2030 partnership and the conditions imposed by their country offices across the world of ‘poverty targeting’.

There is evidence globally that poverty targeting keeps the poor poor, for a variety of reasons.

Some of this evidence is in World Bank publications. And yet, Treasury’s discussions about the R350 SRD in preparation for the MTBPS made mention of the advice of the Bank to move people off the R350 and into (non-existing) jobs.

Poverty is dynamic, you need a safety net that does not disappear the first month you make some money. Rather you need a safety net that provides support as you grow your business and start employing others and start contributing back to the fiscus. If the support is taken away the first time you show a slight income, you will always remain at a survivalist level, and after a while you will decide that it is not worthwhile trying.

The MTBPS will tell where the ANC sees its election priorities for 2024. And all aspiring opposition parties will be watching

© The African [2022]. All rights reserved.